If we are lucky, we get to grow old and suffer the indignities of aging, the aggravation of deteriorating body parts.

Aching old people sometimes don’t feel lucky, of course, and wish they had passed on in their prime. Yet if they had, they would have missed out on the chance to doctor their obituaries! While that doesn’t make up for having to wear adult diapers, it’s some solace.

The other day, I spied the obituary photo of a pretty brunette woman. She appeared to be in her 30s and her rather come-hitherish smile was lovely. I hadn’t known her, but the thought occurred that I wish I had.

What was her sad story—killed in a car wreck after running a marathon? A victim of cancer, leaving behind young children? Stricken down in her yard by climate change? To my dismay, I learned it was none of the above: She died of old age. The pretty young woman passed away in her sleep at age 84!

I’m of two minds about this, about slipping in a photograph from the past to illustrate a contemporary event—ie, death. Celebrities and public officials get away with it because fame is fleeting and public memory is pegged to a particular moment.

For most of us, however, having been famous is not part of our story. We select obit photos with one of two thoughts: Here is how friends of yore will remember us. Or, here is how neighbors and friends today know us. Past and present. Using two photos is an option, I guess, but placing prime and past-prime photographs side by side invites a final indignity. Only the naturally well-preserved dare do it.

Author Wallace Stegner alluded to this then-and-now conundrum in his Pulitzer Prize-winning novel, Angle of Repose. He described aging in terms of the Doppler Effect, in which the sound of an approaching object (or life) has a higher pitch than the sound of its retreat.

Stegner’s character mused: “I would like to hear your life as you heard it, coming at you, instead of hearing it as I do, a somber sound of expectations reduced, desires blunted, hopes deferred or abandoned, chances lost, defeats accepted, griefs borne.”

A mostly lived life indeed is bruised and less hopeful, its potential mostly spent—but that doesn’t mean older men and women are of lesser value. Their worth often is peaking, their accrued wisdom manifested in everything they do and say. Listen and learn.

Of course, some seniors are real dopes. They were dopes as juniors. The point is, one shouldn’t judge a book by its wrinkled, blotched and bent cover. The cover is part of the story.

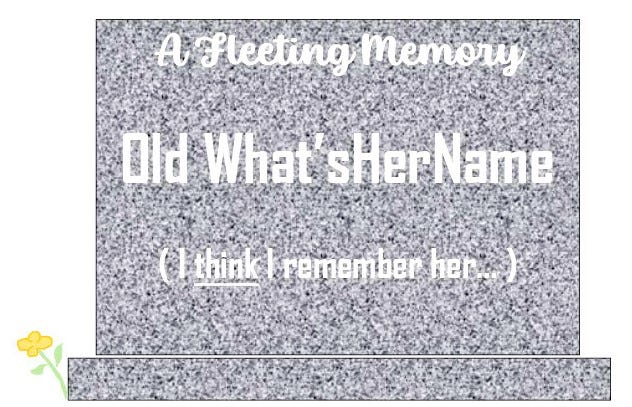

It’s your choice. You can put up a glam obituary photo if you want. You can write an advance obit text in which you are nearly unrecognizable. Fine. But here’s the reality: It won’t much matter. Most people still won’t remember you tomorrow. And that’s OK. Lives are for living, not for being remembered.